Plusieurs associations ont assigné en référé la société Google pour que la justice interdise au moteur de recherche d'associer automatiquement le mot «juif» au nom de personnalités faisant l'objet de requêtes d'internautes. Une audience a été fixée mercredi, à 10h, a annoncé l'avocat de SOS Racisme, Me Patrick Klugman, qui estime que la fonctionnalité «Google Suggest» avait abouti à «la création de ce qui est probablement le plus grand fichier juif de l'histoire».

http://www.letelegramme.com/ig/generales/france-monde/france/google-les-suggestions-du-moteur-de-recherche-font-grincer-des-dents-29-04-2012-1685730.php

samedi 28 avril 2012

dimanche 22 avril 2012

Israeli state funding of Holocaust victims' foundation drops for third year

Over the past year, about 14,000 survivors, nearly 90 percent of whom are over 75, received funding from the organization to cover medical care.

Among those marking Holocaust Remembrance Day beginning on Wednesday evening will be Israel's 198,000 survivors.

While many of them are in financial distress, the state has, for example, been steadily cutting the funding it provides to the Foundation for the Benefit of Holocaust Victims in Israel.

Concentration camp survivor Michael Urich walks along the tracks of Grunewald train station from where the Jews of Berlin were sent to Auschwitz, on Holocaust Remembrance Day 2011 in Berlin, Germany.

| |

| Photo by: AP |

By contrast, the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany, commonly known as the Claims Conference, which negotiated restitution with the German government after World War II, has boosted its financial support of that foundation, which provides economic and other assistance to the survivors. In 2010, the budget of the Foundation for the Benefit of Holocaust Victims was NIS 422 million - NIS 169 million from the Finance Ministry and NIS 253 million from the Claims Conference. Last year, the budget was NIS 399 million, of which NIS 132 million was from the government and NIS 267 million from the claims organization. The trend continued this year: NIS 116 million of the foundation's NIS 429-million budget is from the Israeli government, and NIS 313 million from the Claims Conference. An analysis of the 52,500 people who received assistance last year from the Foundation for the Benefit of Holocaust Victims shows that over 10,000 of them have no children. Fully 54 percent have no living spouse. About 65 percent of those asking for help from the organization were women. The foundation was established in 1994 by the Center of Holocaust Survivor Organizations in Israel, with the backing of the Claims Conference. Over the past year, about 14,000 survivors, nearly 90 percent of whom are over 75, received funding from the organization to cover medical care; by comparison, in 2008, only 40 percent of those assisted were over the age of 75. The most common request, made by more than 40 percent of those seeking assistance, was for financial help for the purchase of medication. Funding for dental care was sought in 37 percent of the cases. Over the past year, the foundation also provided custodial nursing care to nearly 20,000 survivors in the country. There was a decline last year in the number of survivors who received direct assistance of various kinds from the foundation, from about 60,000 in 2010 to 52,500 last year. According to a report from the Myers-JDC-Brookdale Institute, which engages in applied social research, a mere 0.4 percent of Israeli Holocaust survivors are under the age of 70; 44 percent are between 70 and 80; and 55 percent are over 80. The report's authors estimate that by 2025, only 48,000 of the survivors in Israel will still be alive. "The thousands of survivors still among us cannot be allowed to live without dignity," said Elazar Stern, who chairs the Israeli Foundation for the Benefit of Holocaust Victims. "One of our tasks is to see to it that awareness of their needs is translated into means that make assistance to the needy among them possible. The younger generation will not forgive us if we don't care for the members of the older generation with the dignity they deserve."

http://www.haaretz.com/news/national/israeli-state-funding-of-holocaust-victims-foundation-drops-for-third-year-1.424483

samedi 21 avril 2012

Holocaust survivors struggling to make ends meet in Israel

Ros Dayan describes her experience of the Nazis' persecution of Jews in Bulgaria and how she survived the Holocaust. Now living in Israel, she says she doesn't have enough money to buy food or clothes.

Ros is one of a growing proportion of Holocaust survivors in Israel who cannot make ends meet

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/video/2012/apr/19/holocaust-survivor-memorial-day-video

lundi 16 avril 2012

Not All Jews Have Money: Tragedy Inspires New Documentary

Not All Jews Have Money: Tragedy Inspires New Documentary

Apr 16 2012

Do American Jews really have money? That is the burning question that French filmmaker Sasha Andreas (picture above) asks himself after volunteering in a Kibbutz in Israel. He decided to figure this out in a new documentary. “I’m not Jewish myself, but I have met a lot of Jewish people in my life, including when I was in Israel,” Andreas tells Abanibi.“In the kibbutz there were only two or three families who were rich.”

This is how the idea for “Jews got Money,” or as they spell it provocatively, “J£w$ Got Mon€¥”, was born. “My motivation for this film is to debunk the myth that all Jewish people have money. I think it’s a very dangerous cliché and this ignorance fuels hatred.”

Do you have an example of why this prejudice is dangerous?

“There was a story in my home country, France, about the young Ilan Halimi who was kidnapped, tortured and murdered by a gang who assumed that he “had money” because he was a Jew. You and I know, it is not true, many Jewish people have lived and still live in poverty, even in the US.”

For his documentary, currently in pre-production with plans to shoot in New York next month, Andreas is looking to Jewish people living in poverty in New York City and also philanthropists and associations who are focused on helping them. “It is important to talk about solidarity, and it will hopefully help them attract donations,” he says.

“Jews Got Money” will be Andreas’ first documentary. He teamed up with producer Anna Heim, who’s an online journalist at The Next Web, with a background in film & TV distribution, and also involved experienced film editor Ludovic Schoendoerffer (son of late Oscar winner Pierre Schoendoerffer) who lives in Paris. “Our documentary will be in English in order to reach an international audience,” he says, “hopefully on TV and in theaters, but also at festivals and schools around the world.”

For any ideas and interview suggestions you can contact “Jews Got Money” on Twitter: @jewsgottwitt3r or send us an email to write-us@abbanibi.com and we’ll forward it to the production.

http://www.abbanibi.com/blog/not-all-jews-have-money-tragedy-inspires-new-documentary/

samedi 14 avril 2012

$10 million Holocaust survivors' Emergency Fund Launched

(article from 2010)

New York - The Harry and Jeanette Weinberg Foundation, one of the largest private foundations in the United States, announced today that it has established a new, five-year, $10 million grant to fund emergency services for Holocaust survivors residing in North America through the Conference of Jewish Material Claims Against Germany (The Claims Conference). The Weinberg Holocaust Survivors Emergency Assistance Fund (“The Weinberg Fund”) will fund a range of emergency services to survivors, including medical equipment and medications, dental care, transportation, food, and short-term home care.

It is estimated that there are more than 500,000 Holocaust survivors worldwide, with more than 144,000 victims living in North America. The remaining Nazi victims live mostly in Israel and the Former Soviet Union. The average age of a Nazi victim is 79 years with nearly one-quarter of victims 85-years-old or older. One in four aging survivors lives alone in the U.S. and an estimated 37% live at or below the poverty level, a level that is five times the rate of other senior citizens in the U.S.

The Weinberg Fund will provide the financial resources needed to supplement critical services for Holocaust survivors in the communities where they reside. The Weinberg Foundation is one of the largest private Jewish foundations in the U.S., with a mission to fund nonprofits that assist vulnerable populations. For decades, the Foundation has focused much of its efforts within that broad mission on poor older adults and the Jewish community.

“Many aging victims of the Holocaust require assistance to meet their basic needs for shelter, food and medical care,” said Rachel Monroe, president of The Harry and Jeanette Weinberg Foundation. “The grant for emergency assistance is expected to help at least 10,000 Nazi victims living in poverty throughout North America. The Weinberg Foundation remains committed to honoring these courageous men and women whose memories we call upon to educate the world today and for generations to come.”

Judge Ellen M. Heller, a Trustee of the Weinberg Foundation, stated, “The Weinberg Fund gives recognition to the increasing medical and social welfare needs of the aging Jewish Holocaust victims in North America as they enter the final chapter of their lives. No amount of money can compensate these victims of Nazi persecution for the horrors they have suffered. However, the Weinberg Fund will provide crucial assistance and allow these older adults to live out their remaining years with dignity and respect.”

The Weinberg Holocaust Survivor Emergency Assistance Fund will be administered and managed by the highly respected Claims Conference based in New York. The Claims Conference was founded in 1951 when representatives of 23 major national and international Jewish organizations from eight countries met in New York to seek restitution for Jewish victims of the Holocaust. Since its formation, the Claims Conference has continually sought to secure Holocaust-related benefits for victims of the Holocaust resulting in $60 billion in restitution from the German government. Today, the Claims Conference manages grants made by governments and funders throughout the world. The nonprofit has a structure currently in place for emergency assistance grants that will ensure the swift and effective distribution of funds for services.

During the past two decades, the Weinberg Foundation has distributed $6.3 million in grants to 54 different organizations serving Holocaust survivors throughout North America. Upon the conclusion of this grant in 2014, the Weinberg Foundation will have given more than $16 million to support Holocaust survivors in North America. In addition, the Weinberg Foundation has granted millions of dollars to nonprofits that provide direct services to Holocaust survivors and other poor, older adults throughout Israel and the Former Soviet Union, where the majority of survivors reside today.

“The Claims Conference is honored to work in partnership with the Weinberg Foundation to address the increasing needs of elderly Jewish victims of Nazism,” said Julius Berman, chairman of the Claims Conference. “Every day, Holocaust victims with very limited means have to cope with the costs of housing, medicine, food, and other vital needs that they often cannot meet. We hope that the generosity and vision of the Weinberg Foundation will galvanize support for these heroes of the Jewish people.”

Claims Conference Executive Vice President Greg Schneider stated, “Aging Jewish Holocaust victims, abandoned by the world in their youth must now know that they are remembered and cared for in their final years. The Claims Conference is grateful to the Weinberg Foundation for recognizing and responding to the basic needs of so many Nazi victims. Together, we must continue to take on the moral imperative to ensure that Holocaust victims live out their years in a manner befitting the courage and resilience they displayed and the suffering they endured.”

The grant will provide $1 million in 2010, $2.5 million in 2011, 2012, and 2013, and $1.5 million in 2014.

http://www.vosizneias.com/60083/2010/07/14/new-york-10-million-holocaust-survivors-emergency-fund-launched

New York - The Harry and Jeanette Weinberg Foundation, one of the largest private foundations in the United States, announced today that it has established a new, five-year, $10 million grant to fund emergency services for Holocaust survivors residing in North America through the Conference of Jewish Material Claims Against Germany (The Claims Conference). The Weinberg Holocaust Survivors Emergency Assistance Fund (“The Weinberg Fund”) will fund a range of emergency services to survivors, including medical equipment and medications, dental care, transportation, food, and short-term home care.

It is estimated that there are more than 500,000 Holocaust survivors worldwide, with more than 144,000 victims living in North America. The remaining Nazi victims live mostly in Israel and the Former Soviet Union. The average age of a Nazi victim is 79 years with nearly one-quarter of victims 85-years-old or older. One in four aging survivors lives alone in the U.S. and an estimated 37% live at or below the poverty level, a level that is five times the rate of other senior citizens in the U.S.

The Weinberg Fund will provide the financial resources needed to supplement critical services for Holocaust survivors in the communities where they reside. The Weinberg Foundation is one of the largest private Jewish foundations in the U.S., with a mission to fund nonprofits that assist vulnerable populations. For decades, the Foundation has focused much of its efforts within that broad mission on poor older adults and the Jewish community.

“Many aging victims of the Holocaust require assistance to meet their basic needs for shelter, food and medical care,” said Rachel Monroe, president of The Harry and Jeanette Weinberg Foundation. “The grant for emergency assistance is expected to help at least 10,000 Nazi victims living in poverty throughout North America. The Weinberg Foundation remains committed to honoring these courageous men and women whose memories we call upon to educate the world today and for generations to come.”

Judge Ellen M. Heller, a Trustee of the Weinberg Foundation, stated, “The Weinberg Fund gives recognition to the increasing medical and social welfare needs of the aging Jewish Holocaust victims in North America as they enter the final chapter of their lives. No amount of money can compensate these victims of Nazi persecution for the horrors they have suffered. However, the Weinberg Fund will provide crucial assistance and allow these older adults to live out their remaining years with dignity and respect.”

The Weinberg Holocaust Survivor Emergency Assistance Fund will be administered and managed by the highly respected Claims Conference based in New York. The Claims Conference was founded in 1951 when representatives of 23 major national and international Jewish organizations from eight countries met in New York to seek restitution for Jewish victims of the Holocaust. Since its formation, the Claims Conference has continually sought to secure Holocaust-related benefits for victims of the Holocaust resulting in $60 billion in restitution from the German government. Today, the Claims Conference manages grants made by governments and funders throughout the world. The nonprofit has a structure currently in place for emergency assistance grants that will ensure the swift and effective distribution of funds for services.

During the past two decades, the Weinberg Foundation has distributed $6.3 million in grants to 54 different organizations serving Holocaust survivors throughout North America. Upon the conclusion of this grant in 2014, the Weinberg Foundation will have given more than $16 million to support Holocaust survivors in North America. In addition, the Weinberg Foundation has granted millions of dollars to nonprofits that provide direct services to Holocaust survivors and other poor, older adults throughout Israel and the Former Soviet Union, where the majority of survivors reside today.

“The Claims Conference is honored to work in partnership with the Weinberg Foundation to address the increasing needs of elderly Jewish victims of Nazism,” said Julius Berman, chairman of the Claims Conference. “Every day, Holocaust victims with very limited means have to cope with the costs of housing, medicine, food, and other vital needs that they often cannot meet. We hope that the generosity and vision of the Weinberg Foundation will galvanize support for these heroes of the Jewish people.”

Claims Conference Executive Vice President Greg Schneider stated, “Aging Jewish Holocaust victims, abandoned by the world in their youth must now know that they are remembered and cared for in their final years. The Claims Conference is grateful to the Weinberg Foundation for recognizing and responding to the basic needs of so many Nazi victims. Together, we must continue to take on the moral imperative to ensure that Holocaust victims live out their years in a manner befitting the courage and resilience they displayed and the suffering they endured.”

The grant will provide $1 million in 2010, $2.5 million in 2011, 2012, and 2013, and $1.5 million in 2014.

http://www.vosizneias.com/60083/2010/07/14/new-york-10-million-holocaust-survivors-emergency-fund-launched

Loans Without Profit Help Relieve Economic Pain

When Hirshy Minkowicz was growing up in a Hasidic enclave of Brooklyn 30 years ago, he often noticed visitors arriving after dinner to meet with his father. They would withdraw into the study, speak for a time, then part with some confidential agreement having been sealed.

As he grew into his teens, Hirshy came to learn that his father operated a traditional Jewish free-loan program called a gemach. The visitors, many of them teachers in local religious schools, struggling to raise their families on small and irregular salaries, had been coming to borrow money at no interest and with no public exposure.

Now 39 years old and serving as the rabbi of a Chabad center near Atlanta, Rabbi Minkowicz has done something he never expected: open a gemach that deals primarily with non-Orthodox Jews in a prosperous stretch of suburbia. The reason, quite simply, is the prolonged downturn in the American economy, which has driven up the number of Jews identified by one poverty expert as the “middle-class needy.”

The same phenomenon has appeared in Jewish communities across the country, albeit most often in those with existing Orthodox populations already familiar with the gemach system. This institution, rooted in biblical and Talmudic teachings and whose name is a contraction of the Hebrew words for “bestowal of kindness” (“gemilut chasadim”), is now meeting needs created by such resolutely modern causes as subprime mortgages, outsourcing and credit default swaps.

“I honestly never thought, in my realm here, to start a gemach,” Rabbi Minkowicz said in a recent interview. “I thought people wouldn’t understand it. It’d be a foreign concept. They hadn’t grown up that way. But definitely, definitely, definitely the economy now is the worst. The 13 years I’ve been here, I’ve never seen people go from a regular life to rags. I’ve seen that up-front and personal.”

It is difficult to determine the exact dimensions of the economy’s impact on the Jewish population in general and on the surge in the use of gemachs specifically. The loan programs, often financed and run by families, operate on the basis of anonymity. Governmental statistics on poverty, unemployment, foreclosure and other such measures of the continuing malaise are not broken down by religion, as they are by race.

Still, the evidence points to an economic toll on Jews — not severe enough in most cases to plunge them into homelessness and destitution, or to qualify them for food stamps and Medicaid, but deep enough to destabilize what had been securely middle-class lives. Since the stock market collapse in late 2008 pushed the nation into recession, the demand for food and clothes from Jewish social service agencies and charities has risen by roughly 40 percent, according to their administrators.

“This area of the middle-class needy has just exploded,” said William E. Rapfogel, the chief executive of the Metropolitan Council on Jewish Poverty, which covers the New York area. “We’ve seen people who were making $75,000, even $200,000, lose a substantial portion of income. When they lose a job, they get another, but it’s a job for less. They’re so over-leveraged in their homes, they can’t get out. If they sold, they wouldn’t take out a nickel.”

On Staten Island, the borough of New York most akin to a suburb, Rabbi Moshe Meir Weiss of the Agudas Yisroel synagogue has seen that situation. In the past, Jews in his community used gemachs primarily to borrow items they needed for only a limited time: a wedding dress, rubber bins for moving furniture, a wig to cover hair lost to chemotherapy, even breast milk for a nursing child. Over the last several years, however, the gemachs have increasingly dispensed cash loans and groceries.

“People have been so taken by shock,” Rabbi Weiss said. “Picture yourself, God forbid, having to take a can of tuna from someone. It’s almost like the soup lines of the Great Depression.”

The gemach system, however, offers two tangible differences. First, as a matter of religious teaching and longstanding custom, a gemach makes no profit on its loans. Second, the tradition of confidentiality, rooted in Judaic commentaries about giving and receiving charity, allows a supplicant to save face.

“When it’s within your own group, it’s less embarrassing,” Rabbi Weiss said. “You feel your compadre understands and is doing it out of love.”

In suburban Atlanta, Rabbi Minkowicz had similar thoughts in mind last August, when a congregant approached him with an idealistic but unformed proposal. The man had seen the toll that corporate layoffs and the cratered housing market had taken on the local Jewish community. He and his wife, both professionals in public-sector jobs, had saved $5,000 to do something about it. Their question was what.

At that point, Rabbi Minkowicz explained about gemach, a word the donor had never heard. What impressed the man immediately, in this era of celebrity charities and naming rights, was the quality of humility. A borrower would not be subjected to a credit check or required to put up collateral, only to have another member of the Jewish community co-sign. The donor could remain unknown.

“I could help people without seeming like I’m showing off,” the man said. Indeed, he spoke for this column only on the promise that his identity not be revealed.

By now, four months later, the resulting gemach has made two loans of about $1,000 apiece, with a third imminent. As those borrowers repay the gemach, at the rate of roughly $100 a month, Rabbi Minkowicz can in turn recycle the money to others who need it.

All of which puts him in mind of those knocks on the door in Brooklyn decades ago, and of the decorous way his father answered. “I’ve tried to use the same model I saw,” Rabbi Minkowicz put it. “You help the people who are struggling. And you try to preserve their dignity.”

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/03/us/a-traditional-jewish-loan-program-helps-ease-pain-of-tough-economic-times.html

As he grew into his teens, Hirshy came to learn that his father operated a traditional Jewish free-loan program called a gemach. The visitors, many of them teachers in local religious schools, struggling to raise their families on small and irregular salaries, had been coming to borrow money at no interest and with no public exposure.

Now 39 years old and serving as the rabbi of a Chabad center near Atlanta, Rabbi Minkowicz has done something he never expected: open a gemach that deals primarily with non-Orthodox Jews in a prosperous stretch of suburbia. The reason, quite simply, is the prolonged downturn in the American economy, which has driven up the number of Jews identified by one poverty expert as the “middle-class needy.”

The same phenomenon has appeared in Jewish communities across the country, albeit most often in those with existing Orthodox populations already familiar with the gemach system. This institution, rooted in biblical and Talmudic teachings and whose name is a contraction of the Hebrew words for “bestowal of kindness” (“gemilut chasadim”), is now meeting needs created by such resolutely modern causes as subprime mortgages, outsourcing and credit default swaps.

“I honestly never thought, in my realm here, to start a gemach,” Rabbi Minkowicz said in a recent interview. “I thought people wouldn’t understand it. It’d be a foreign concept. They hadn’t grown up that way. But definitely, definitely, definitely the economy now is the worst. The 13 years I’ve been here, I’ve never seen people go from a regular life to rags. I’ve seen that up-front and personal.”

It is difficult to determine the exact dimensions of the economy’s impact on the Jewish population in general and on the surge in the use of gemachs specifically. The loan programs, often financed and run by families, operate on the basis of anonymity. Governmental statistics on poverty, unemployment, foreclosure and other such measures of the continuing malaise are not broken down by religion, as they are by race.

Still, the evidence points to an economic toll on Jews — not severe enough in most cases to plunge them into homelessness and destitution, or to qualify them for food stamps and Medicaid, but deep enough to destabilize what had been securely middle-class lives. Since the stock market collapse in late 2008 pushed the nation into recession, the demand for food and clothes from Jewish social service agencies and charities has risen by roughly 40 percent, according to their administrators.

“This area of the middle-class needy has just exploded,” said William E. Rapfogel, the chief executive of the Metropolitan Council on Jewish Poverty, which covers the New York area. “We’ve seen people who were making $75,000, even $200,000, lose a substantial portion of income. When they lose a job, they get another, but it’s a job for less. They’re so over-leveraged in their homes, they can’t get out. If they sold, they wouldn’t take out a nickel.”

On Staten Island, the borough of New York most akin to a suburb, Rabbi Moshe Meir Weiss of the Agudas Yisroel synagogue has seen that situation. In the past, Jews in his community used gemachs primarily to borrow items they needed for only a limited time: a wedding dress, rubber bins for moving furniture, a wig to cover hair lost to chemotherapy, even breast milk for a nursing child. Over the last several years, however, the gemachs have increasingly dispensed cash loans and groceries.

“People have been so taken by shock,” Rabbi Weiss said. “Picture yourself, God forbid, having to take a can of tuna from someone. It’s almost like the soup lines of the Great Depression.”

The gemach system, however, offers two tangible differences. First, as a matter of religious teaching and longstanding custom, a gemach makes no profit on its loans. Second, the tradition of confidentiality, rooted in Judaic commentaries about giving and receiving charity, allows a supplicant to save face.

“When it’s within your own group, it’s less embarrassing,” Rabbi Weiss said. “You feel your compadre understands and is doing it out of love.”

In suburban Atlanta, Rabbi Minkowicz had similar thoughts in mind last August, when a congregant approached him with an idealistic but unformed proposal. The man had seen the toll that corporate layoffs and the cratered housing market had taken on the local Jewish community. He and his wife, both professionals in public-sector jobs, had saved $5,000 to do something about it. Their question was what.

At that point, Rabbi Minkowicz explained about gemach, a word the donor had never heard. What impressed the man immediately, in this era of celebrity charities and naming rights, was the quality of humility. A borrower would not be subjected to a credit check or required to put up collateral, only to have another member of the Jewish community co-sign. The donor could remain unknown.

“I could help people without seeming like I’m showing off,” the man said. Indeed, he spoke for this column only on the promise that his identity not be revealed.

By now, four months later, the resulting gemach has made two loans of about $1,000 apiece, with a third imminent. As those borrowers repay the gemach, at the rate of roughly $100 a month, Rabbi Minkowicz can in turn recycle the money to others who need it.

All of which puts him in mind of those knocks on the door in Brooklyn decades ago, and of the decorous way his father answered. “I’ve tried to use the same model I saw,” Rabbi Minkowicz put it. “You help the people who are struggling. And you try to preserve their dignity.”

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/03/us/a-traditional-jewish-loan-program-helps-ease-pain-of-tough-economic-times.html

Food Bank For New York City Launches Passover Virtual Food Drive

New York - This year food charities are using a new tool to bust old myths about who they serve across the city and in the Bronx.

The Food Bank for New York City has launched a Passover virtual food drive, which lets donors choose what kosher foods they will give to struggling Jewish neighbors, just as if they were doing online grocery shopping.

It also lets people know that hunger affects those of every creed and culture.

“Tools like the virtual food drive allow us to tell a better story about who is hungry,” said Food Bank President and CEO Margarette Purvis. “So many people still believe we are only serving homeless people. No. It’s people with college degrees, people who lost a job. It’s everyday people.

Thousands of Hanukkah and Passover meals are distributed each year by the Bronx Jewish Community Council, mostly to homebound seniors without families to celebrate holidays with them.

BJCC’s Director of Operations, Rose Turshen, said she hopes the online food drive will get young people thinking about this forgotten population.

“We are really excited about this virtual food drive,” Turshen said. “I think this is really unique and innovative. My generation, we don’t write checks.”

Turshen is 28. She said younger people are more likely to donate online, she said. “I really think this is going to drive some new online donations.”

A holiday like Passover, during which observant Jews must stock their kitchens entirely with kosher food, can create a devastating expense for people quietly struggling with poverty, Purvis said.

The Food Bank will give all proceeds from the drive to the Metropolitan Council on Jewish Poverty, which fed more than 50,000 Jewish families last Passover. This year the Met Council has committed to provide more than 2 million pounds of Kosher food to needy Jewish families.

To donate, visit the Food Bank’s website at http://www.foodbanknyc.org/.

http://www.vosizneias.com/103634/2012/03/26/new-york-food-bank-for-new-york-city-launches-passover-virtual-food-drive/

The Food Bank for New York City has launched a Passover virtual food drive, which lets donors choose what kosher foods they will give to struggling Jewish neighbors, just as if they were doing online grocery shopping.

It also lets people know that hunger affects those of every creed and culture.

“Tools like the virtual food drive allow us to tell a better story about who is hungry,” said Food Bank President and CEO Margarette Purvis. “So many people still believe we are only serving homeless people. No. It’s people with college degrees, people who lost a job. It’s everyday people.

Thousands of Hanukkah and Passover meals are distributed each year by the Bronx Jewish Community Council, mostly to homebound seniors without families to celebrate holidays with them.

BJCC’s Director of Operations, Rose Turshen, said she hopes the online food drive will get young people thinking about this forgotten population.

“We are really excited about this virtual food drive,” Turshen said. “I think this is really unique and innovative. My generation, we don’t write checks.”

Turshen is 28. She said younger people are more likely to donate online, she said. “I really think this is going to drive some new online donations.”

A holiday like Passover, during which observant Jews must stock their kitchens entirely with kosher food, can create a devastating expense for people quietly struggling with poverty, Purvis said.

The Food Bank will give all proceeds from the drive to the Metropolitan Council on Jewish Poverty, which fed more than 50,000 Jewish families last Passover. This year the Met Council has committed to provide more than 2 million pounds of Kosher food to needy Jewish families.

To donate, visit the Food Bank’s website at http://www.foodbanknyc.org/.

http://www.vosizneias.com/103634/2012/03/26/new-york-food-bank-for-new-york-city-launches-passover-virtual-food-drive/

Cash-strapped Jewish families will get pre-paid debit cards to pay Passover costs

Without help, many Jewish families in New York could not afford to properly observe Passover.

With that in mind, about 15,000 homes will be issued pre-paid debit cards — worth $50 to $300 depending on family size — to defray the cost of special holiday preparations that center around avoiding leavened foods.

It’s the first time the Metropolitan Council on Jewish Poverty is issuing the American Express cards, asking 60 sites — including their 25 satellite neighborhood Jewish Community Councils — to spread the word among local families.

“There is a sense that Jewish poverty is an oxymoron, people don’t think that there are poor Jews out there,” said Met Council CEO Willie Rapfogel. “Passover is a time of year when people ask for help. Everything in the ‘fridge and pantry can’t be used. They need everything.”

Religious law requires that people scrub their homes clean before Passover - removing any signs of starchy foods and then replacing normal kitchen supplies with sets that have never touched banned food and provisions.

A family of four can easily drop $1,000 on groceries and fresh pots and pans in preparation for the eight-day holiday, Rapfogel said.

“It’s hard. We don’t qualify for Medicaid or food stamps,” said Esti Rosenblatt, 30, using a $200 card to shop near her Crown Heights home. “We just had to sell our car.”

Rosenblatt, 30, a part-time nonprofit coordinator, and her husband Itamar, 33, a social worker, were already struggling to pay the mortgage on their three-bedroom condo and cover treatments for their 5-year-old son

Shmuel, who suffers from eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorder (EGID).

“Any help this time of year helps,” Rosenblatt said.

Washington Heights resident Michael Vaystub, 70, said he and his 69-year-old wife just do get by on Social Security. He said they’ll use their $100 card to purchase enough matzoh ball soup and gefilte fish to get them through the holiday.

“The price in stores are up. And the money is down,” Vaystub. “That’s why having this card is very important.”

Before the cards, Met Council allowed people to use paper vouchers at kosher grocery shops across the city.

“The voucher was too complicated. Our customers speak Russian and they didn’t understand what items they could get,” said Michael Jaffe, owner of Kosher Palace in Sheepshead Bay, one of 60 stores and shops that will honor the special debit cards.

http://articles.nydailynews.com/2012-04-03/news/31282996_1_debit-cards-passover-family-size

With that in mind, about 15,000 homes will be issued pre-paid debit cards — worth $50 to $300 depending on family size — to defray the cost of special holiday preparations that center around avoiding leavened foods.

It’s the first time the Metropolitan Council on Jewish Poverty is issuing the American Express cards, asking 60 sites — including their 25 satellite neighborhood Jewish Community Councils — to spread the word among local families.

“There is a sense that Jewish poverty is an oxymoron, people don’t think that there are poor Jews out there,” said Met Council CEO Willie Rapfogel. “Passover is a time of year when people ask for help. Everything in the ‘fridge and pantry can’t be used. They need everything.”

Religious law requires that people scrub their homes clean before Passover - removing any signs of starchy foods and then replacing normal kitchen supplies with sets that have never touched banned food and provisions.

A family of four can easily drop $1,000 on groceries and fresh pots and pans in preparation for the eight-day holiday, Rapfogel said.

“It’s hard. We don’t qualify for Medicaid or food stamps,” said Esti Rosenblatt, 30, using a $200 card to shop near her Crown Heights home. “We just had to sell our car.”

Rosenblatt, 30, a part-time nonprofit coordinator, and her husband Itamar, 33, a social worker, were already struggling to pay the mortgage on their three-bedroom condo and cover treatments for their 5-year-old son

Shmuel, who suffers from eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorder (EGID).

“Any help this time of year helps,” Rosenblatt said.

Washington Heights resident Michael Vaystub, 70, said he and his 69-year-old wife just do get by on Social Security. He said they’ll use their $100 card to purchase enough matzoh ball soup and gefilte fish to get them through the holiday.

“The price in stores are up. And the money is down,” Vaystub. “That’s why having this card is very important.”

Before the cards, Met Council allowed people to use paper vouchers at kosher grocery shops across the city.

“The voucher was too complicated. Our customers speak Russian and they didn’t understand what items they could get,” said Michael Jaffe, owner of Kosher Palace in Sheepshead Bay, one of 60 stores and shops that will honor the special debit cards.

http://articles.nydailynews.com/2012-04-03/news/31282996_1_debit-cards-passover-family-size

mercredi 11 avril 2012

Hungry for soup kitchens: 3 new Masbias set for Jewish nabes in Brooklyn and Queens

When the kosher soup kitchen Masbia opened in Borough Park nearly four years ago, it served a total of eight patrons.

"Now, we have nights when we go over 200," said Alexander Rapaport, Masbia's executive director. And the need is growing.

With hunger and poverty growing in the Jewish community, Masbia is now planning to open three more kosher soup kitchens - two in Brooklyn and one in Queens. The first on Lee St. in Williamsburg is expected to open in June.

Among Jewish communities in Brooklyn, Williamsburg has the highest level of poverty, with 64% of households earning less than $35,000, according to a UJA-Federation study.

The council is looking for a second site somewhere in southern Brooklyn to serve needy residents in Midwood, Flatbush, Sheepshead Bay, Brighton Beach and Coney Island.

The third kitchen will be in central Queens to serve Jackson Heights, Rego Park, Forest Hills and Kew Gardens.

"We're focusing on the areas with the highest concentrations of poor, working poor and middle-class people who have lost jobs and can't make ends meet," said William Rapfogel, director of Metropolitan Council on Jewish Poverty, which is partnering with Masbia in operating the soup kitchens.

The new facilities will be patterned after Masbia, which is set up like a restaurant, with artificial plants surrounding tables to offer diners a sense of privacy.

"This is about making sure people have a dignified way to have a meal in a clean, safe environment," Rapfogel said.

Social workers will regularly visit to make sure diners take advantage of other services they might be eligible for, such as children's insurance or Medicaid.

Rapaport said he was concerned particularly about the increasing numbers of children being brought to Masbia for meals. On a recent night, he counted 61 youngsters.

"We used to average around 20 a day," Rapaport said.

The downturn in the economy has led to a rise in middle-class diners at Masbia, Rapaport said. "Their shame is so much bigger. They don't know where to call for food stamps. They don't know where food pantries are. People have just fallen into this situation."

http://www.nydailynews.com/new-york/brooklyn/hungry-soup-kitchens-3-masbias-set-jewish-nabes-brooklyn-queens-article-1.367725#ixzz1rmZLnLcx

"Now, we have nights when we go over 200," said Alexander Rapaport, Masbia's executive director. And the need is growing.

With hunger and poverty growing in the Jewish community, Masbia is now planning to open three more kosher soup kitchens - two in Brooklyn and one in Queens. The first on Lee St. in Williamsburg is expected to open in June.

Among Jewish communities in Brooklyn, Williamsburg has the highest level of poverty, with 64% of households earning less than $35,000, according to a UJA-Federation study.

The council is looking for a second site somewhere in southern Brooklyn to serve needy residents in Midwood, Flatbush, Sheepshead Bay, Brighton Beach and Coney Island.

The third kitchen will be in central Queens to serve Jackson Heights, Rego Park, Forest Hills and Kew Gardens.

"We're focusing on the areas with the highest concentrations of poor, working poor and middle-class people who have lost jobs and can't make ends meet," said William Rapfogel, director of Metropolitan Council on Jewish Poverty, which is partnering with Masbia in operating the soup kitchens.

The new facilities will be patterned after Masbia, which is set up like a restaurant, with artificial plants surrounding tables to offer diners a sense of privacy.

"This is about making sure people have a dignified way to have a meal in a clean, safe environment," Rapfogel said.

Social workers will regularly visit to make sure diners take advantage of other services they might be eligible for, such as children's insurance or Medicaid.

Rapaport said he was concerned particularly about the increasing numbers of children being brought to Masbia for meals. On a recent night, he counted 61 youngsters.

"We used to average around 20 a day," Rapaport said.

The downturn in the economy has led to a rise in middle-class diners at Masbia, Rapaport said. "Their shame is so much bigger. They don't know where to call for food stamps. They don't know where food pantries are. People have just fallen into this situation."

http://www.nydailynews.com/new-york/brooklyn/hungry-soup-kitchens-3-masbias-set-jewish-nabes-brooklyn-queens-article-1.367725#ixzz1rmZLnLcx

Soup kitchens will be kosher, classy

An upscale Midwood kosher restaurant that closed in May will soon reopen as a kosher soup kitchen, offering a fine dining experience, complete with waiter service.

Orthodox Jews will be treated to food prepared by a self-taught chef who has never cooked outside the home.

But chef Aaron Sender, 34, landed the job at Masbia with a can-do attitude and belief in community building through eating. "Breaking bread with people and sharing in a joyful, celebratory way is something that's really nourishing," said Sender, who grew up in Borough Park.

Despite his inexperience, Sender will soon be cooking hundreds of meals a day for Masbia's new locations in Midwood, Williamsburg and Rego Park - all set to open in the coming weeks - and its existing site in Borough Park.

The five-course dinners will be prepared in Midwood, then delivered to the other soup kitchens, which are modeled after restaurants, with dividers to provide privacy, and will include waiters to make the experience feel more dignified.

"We think so many people don't come because they're embarrassed," said Masbia Executive Director Alexander Rapaport. "But it's going to be uplifting for them."

Rapaport was not worried about Sender's culinary background, because mass producing food doesn't require as much skill as fine dining.

"When you think of a restaurant, you think of a menu with fancy recipes. But in a soup kitchen, you just cook bulk."

Sender, whose resume includes stints as a science journalist and a laborer on an organic farm, was slightly nervous about the task ahead of him, but promised success.

"I'm an improviser," he said. "I'll do whatever it takes."

Two or three other workers will assist him in the galley.

Most dinners will consist of chicken, mashed potatoes, another vegetable side, soup and dessert, but Sender hopes to eventually include diverse ethnic cuisine.

Officials from Masbia decided to expand their services into other neighborhoods when they saw hunger and poverty growing in Jewish communities.

Rabbi David Niederman, executive director of the United Jewish Organizations of Williamsburg, said his group, which runs a food pantry, is delivering hundreds more meals per week than last year.

"So many families are almost in chaos," said William Rapfogel, executive director of the Metropolitan Council on Jewish Poverty, which is providing funding for Masbia's expansion. "We're seeing people who've never had a financial problem in their entire lives."

http://www.nydailynews.com/new-york/brooklyn/soup-kitchens-kosher-classy-article-1.419860#ixzz1rmXlQzdR

Orthodox Jews will be treated to food prepared by a self-taught chef who has never cooked outside the home.

But chef Aaron Sender, 34, landed the job at Masbia with a can-do attitude and belief in community building through eating. "Breaking bread with people and sharing in a joyful, celebratory way is something that's really nourishing," said Sender, who grew up in Borough Park.

Despite his inexperience, Sender will soon be cooking hundreds of meals a day for Masbia's new locations in Midwood, Williamsburg and Rego Park - all set to open in the coming weeks - and its existing site in Borough Park.

The five-course dinners will be prepared in Midwood, then delivered to the other soup kitchens, which are modeled after restaurants, with dividers to provide privacy, and will include waiters to make the experience feel more dignified.

"We think so many people don't come because they're embarrassed," said Masbia Executive Director Alexander Rapaport. "But it's going to be uplifting for them."

Rapaport was not worried about Sender's culinary background, because mass producing food doesn't require as much skill as fine dining.

"When you think of a restaurant, you think of a menu with fancy recipes. But in a soup kitchen, you just cook bulk."

Sender, whose resume includes stints as a science journalist and a laborer on an organic farm, was slightly nervous about the task ahead of him, but promised success.

"I'm an improviser," he said. "I'll do whatever it takes."

Two or three other workers will assist him in the galley.

Most dinners will consist of chicken, mashed potatoes, another vegetable side, soup and dessert, but Sender hopes to eventually include diverse ethnic cuisine.

Officials from Masbia decided to expand their services into other neighborhoods when they saw hunger and poverty growing in Jewish communities.

Rabbi David Niederman, executive director of the United Jewish Organizations of Williamsburg, said his group, which runs a food pantry, is delivering hundreds more meals per week than last year.

"So many families are almost in chaos," said William Rapfogel, executive director of the Metropolitan Council on Jewish Poverty, which is providing funding for Masbia's expansion. "We're seeing people who've never had a financial problem in their entire lives."

http://www.nydailynews.com/new-york/brooklyn/soup-kitchens-kosher-classy-article-1.419860#ixzz1rmXlQzdR

mardi 10 avril 2012

Jewish Poverty Deepens in New York City

Both the depth and distribution of Jewish poverty in New York City has increased during the past decade, according to a new study.

The study found that nearly 60% of Jews living in Brooklyn’s heavily ultra-Orthodox Williamsburg neighborhood live in poverty.

More surprising to some observers is the finding that the number of poor has risen sharply in both the Bronx and Queens, outside historic centers of Jewish poverty in Brooklyn.

These findings were contained in a new study of Jewish poverty unveiled Tuesday at the offices of the UJA-Federation of New York, which sponsored the work along with the Metropolitan Council on Jewish Poverty. The “Report on Jewish Poverty” is a detailed analysis of the preliminary poverty figures given in the Jewish Community Study of New York, which was released last summer and was based on phone interviews from 2002.

Many activists in the Jewish community were shocked by the finding that nearly 21% of Jews in New York City live at less than 150% of the federal poverty line, the standard used to define poverty in this study. That amounts to $13,290 for a one-person household and $27, 150 for a four-person household.

That figure represented a sharp rise from the levels of Jewish poverty in 1991, when the last study was done.

Another 10%, or 104,000 New York-area Jews, live in households with incomes of less than $35,000 a year, and report they are struggling to “make ends meet.” Experts say this group of near poor is often more vulnerable than the poor because they are ineligible for government benefits.

The more detailed examination unveiled this week found higher levels of poverty in vulnerable neighborhoods, as well as an increasing spread of poverty in New York beyond the traditional centers of poor Jews.

Communal leaders and poverty experts in attendance at the meeting this week were not optimistic about the new findings.

“This conference is in itself kind of disappointing,” said Menachem Lubinsky, the former president of the Metropolitan Council on Jewish Poverty. “When I was young and idealistic, I believed that in the future a conference on Jewish poverty would not be needed.”

Instead, as presenter after presenter stressed, while the overall poverty level in New York City has declined over the past 10 years, poverty in the Jewish community has increased by 54%. The elderly, large Orthodox families and recent immigrants from the former Soviet Union account for more than 84% of the Jewish poor in New York.

That these groups were suffering the most did not come as a surprise to anti-poverty activists. But the intense levels of poverty came as a shock to many communal leaders. About 85% of Russian immigrants over the age of 65 live in poverty. In five neighborhoods with large immigrant and Orthodox communities, including Williamsburg, the rate of poverty jumped to more than 30%.

But the Jewish poor were not restricted to the old loci of poverty. The study found that in absolute terms, the greatest number of Jewish poor — 97,000 — were among working-age adults. The percentage of Jewish poor in both the Bronx and Queens doubled to 19%. Particularly in Queens, which has 42,700 Jews living in poverty, the study found that many of the poor were isolated from any Jewish communal organizations that might be able to help them.

The sharp rise in both the depth and distribution of Jewish poverty was attributed by the study’s authors, David Grossman and Jacob Ukeles, to the almost 105,000 Russian immigrants who moved to New York during the last 10 years, many of whom arrived nearly penniless.

When discussing the statistics on this immigrant community, Ukeles and Grossman departed from the general pessimism of the day. While the elderly immigrants are still overwhelmingly poor, the poverty level for young adults, ages 18 to 34, is only 29%, suggesting that many are discovering the quick economic success that had been a trademark of earlier Jewish immigrant communities.

In addition, Ukeles and Grossman gave a slightly more encouraging spin to one of the most discouraging findings of last summer’s report, which suggested that the Jewish poverty rate in New York City doubled, or rose 100%, during the past 10 years. The authors now say that because of changes in calculating methods, the percentage of increase should actually be lowered to 54%.

The most hopeful information for most attendees, though, was the mere appearance of the study itself, which they hope will focus renewed attention on poverty, a problem that many communal leaders say remains hidden to most of the community. This detailed study is one of only two or three community poverty studies in the United States, according to Ukeles.

The detailed poverty statistics will also help Jewish organizations improve their services to the poor, said Alisa Rubin Kurshan, vice president for strategic planning at UJA-Federation. “It’s only once you have such detailed data that you can make the proper programming choices,” she said.

http://www.forward.com/articles/6262/jewish-poverty-deepens-in-new-york-city/#ixzz1rdlb7TEV

The study found that nearly 60% of Jews living in Brooklyn’s heavily ultra-Orthodox Williamsburg neighborhood live in poverty.

More surprising to some observers is the finding that the number of poor has risen sharply in both the Bronx and Queens, outside historic centers of Jewish poverty in Brooklyn.

These findings were contained in a new study of Jewish poverty unveiled Tuesday at the offices of the UJA-Federation of New York, which sponsored the work along with the Metropolitan Council on Jewish Poverty. The “Report on Jewish Poverty” is a detailed analysis of the preliminary poverty figures given in the Jewish Community Study of New York, which was released last summer and was based on phone interviews from 2002.

Many activists in the Jewish community were shocked by the finding that nearly 21% of Jews in New York City live at less than 150% of the federal poverty line, the standard used to define poverty in this study. That amounts to $13,290 for a one-person household and $27, 150 for a four-person household.

That figure represented a sharp rise from the levels of Jewish poverty in 1991, when the last study was done.

Another 10%, or 104,000 New York-area Jews, live in households with incomes of less than $35,000 a year, and report they are struggling to “make ends meet.” Experts say this group of near poor is often more vulnerable than the poor because they are ineligible for government benefits.

The more detailed examination unveiled this week found higher levels of poverty in vulnerable neighborhoods, as well as an increasing spread of poverty in New York beyond the traditional centers of poor Jews.

Communal leaders and poverty experts in attendance at the meeting this week were not optimistic about the new findings.

“This conference is in itself kind of disappointing,” said Menachem Lubinsky, the former president of the Metropolitan Council on Jewish Poverty. “When I was young and idealistic, I believed that in the future a conference on Jewish poverty would not be needed.”

Instead, as presenter after presenter stressed, while the overall poverty level in New York City has declined over the past 10 years, poverty in the Jewish community has increased by 54%. The elderly, large Orthodox families and recent immigrants from the former Soviet Union account for more than 84% of the Jewish poor in New York.

That these groups were suffering the most did not come as a surprise to anti-poverty activists. But the intense levels of poverty came as a shock to many communal leaders. About 85% of Russian immigrants over the age of 65 live in poverty. In five neighborhoods with large immigrant and Orthodox communities, including Williamsburg, the rate of poverty jumped to more than 30%.

But the Jewish poor were not restricted to the old loci of poverty. The study found that in absolute terms, the greatest number of Jewish poor — 97,000 — were among working-age adults. The percentage of Jewish poor in both the Bronx and Queens doubled to 19%. Particularly in Queens, which has 42,700 Jews living in poverty, the study found that many of the poor were isolated from any Jewish communal organizations that might be able to help them.

The sharp rise in both the depth and distribution of Jewish poverty was attributed by the study’s authors, David Grossman and Jacob Ukeles, to the almost 105,000 Russian immigrants who moved to New York during the last 10 years, many of whom arrived nearly penniless.

When discussing the statistics on this immigrant community, Ukeles and Grossman departed from the general pessimism of the day. While the elderly immigrants are still overwhelmingly poor, the poverty level for young adults, ages 18 to 34, is only 29%, suggesting that many are discovering the quick economic success that had been a trademark of earlier Jewish immigrant communities.

In addition, Ukeles and Grossman gave a slightly more encouraging spin to one of the most discouraging findings of last summer’s report, which suggested that the Jewish poverty rate in New York City doubled, or rose 100%, during the past 10 years. The authors now say that because of changes in calculating methods, the percentage of increase should actually be lowered to 54%.

The most hopeful information for most attendees, though, was the mere appearance of the study itself, which they hope will focus renewed attention on poverty, a problem that many communal leaders say remains hidden to most of the community. This detailed study is one of only two or three community poverty studies in the United States, according to Ukeles.

The detailed poverty statistics will also help Jewish organizations improve their services to the poor, said Alisa Rubin Kurshan, vice president for strategic planning at UJA-Federation. “It’s only once you have such detailed data that you can make the proper programming choices,” she said.

http://www.forward.com/articles/6262/jewish-poverty-deepens-in-new-york-city/#ixzz1rdlb7TEV

A Bronx Tale.

After the congregants of an Orthodox synagogue could no longer afford their rent, they found help in the local mosque.

Near the corner of Westchester Avenue and Pugsley Street in Parkchester, just off the elevated tracks of the No. 6 train, Yaakov Wayne Baumann stood outside a graffiti-covered storefront on a chilly Saturday morning. Suited up in a black overcoat with a matching wide-brimmed black fedora, the thickly bearded 42-year-old chatted with elderly congregants as they entered the building for Shabbat service.

The only unusual detail: This synagogue is a mosque.

Or rather, it’s housed inside a mosque. That’s right: Members of the Chabad of East Bronx, an ultra-Orthodox synagogue, worship in the Islamic Cultural Center of North America, which is home to the Al-Iman mosque.

“People have a misconception that Muslims hate Jews,” said Baumann. “But here is an example of them working with us.”

Indeed, though conventionally viewed as adversaries both here and abroad, the Jews and Muslims of the Bronx have been propelled into an unlikely bond by a demographic shift. The borough was once home to an estimated 630,000 Jews, but by 2002 that number had dropped to 45,100, according to a study by the Jewish Community Relations Council. At the same time, the Muslim population has been increasing. In Parkchester alone, there are currently five mosques, including Masjid Al-Iman.

“Nowhere in the world would Jews and Muslims be meeting under the same roof,” said Patricia Tomasulo, the Catholic Democratic precinct captain and Parkchester community organizer, who first introduced the leaders of the synagogue and mosque to each other. “It’s so unique.”

The relationship started years ago, when the Young Israel Congregation, then located on Virginia Avenue in Parkchester, was running clothing drives for needy families, according to Leon Bleckman, now 78, who was at the time the treasurer of the congregation. One of the recipients was Sheikh Moussa Drammeh, the founder of the Al-Iman Mosque, who was collecting donations for his congregants—many of whom are immigrants from Africa. The 49-year-old imam is an immigrant from Gambia in West Africa who came to the United States in 1986. After a year in Harlem, he moved to Parkchester, where he eventually founded the Muslim center and later established an Islamic grade school. Through that initial meeting, a rapport developed between the two houses of worship, and the synagogue continued to donate to the Islamic center, among other organizations.

But in 2003, after years of declining membership, Young Israel was forced to sell its building at 1375 Virginia Ave., according to a database maintained by Yeshiva University, which keeps historical records of synagogues. Before the closing, non-religious items were given away; in fact, among the beneficiaries was none other than Drammeh, who took some chairs and tables for his center.

Meanwhile, Bleckman and the remaining members moved to a nearby storefront location, renting it for $2,000 a month including utilities. With mostly elderly congregants, Young Israel struggled to survive financially and, at the end of 2007, was forced to close for good. The remaining congregants were left without a place to pray. During the synagogue’s farewell service, four young men from the Chabad Lubavitch world headquarters in Crown Heights showed up. Three months earlier, Bleckman, then chairman of the synagogue’s emergency fund, had appealed for help from the Chabad.

“The boys from the Chabad said they came to save us,” said Bleckman. “We were crying.”

At this point, Chabad took over the congregational reins from Young Israel, with members officially adopting the new name Chabad of East Bronx. Still, for the next six to seven weeks, Bleckman said they could not even hold a service because they had nowhere to hold it.

When Drammeh learned of their plight, he immediately volunteered to accommodate them at the Muslim center at 2006 Westchester Ave.—for free.

“They don’t pay anything, because these are old folks whose income are very limited now,” said Drammeh, adding that he felt it was his turn to help the people who had once helped him and his community. “Not every Muslim likes us, because not every Muslim believes that Muslims and Jews should be like this,” Drammeh said, referring to the shared space. But “there’s no reason why we should hate each other, why we cannot be families.” Drammeh in particular admires the dedication of the Chabad rabbis, who walked 15 miles from Brooklyn every Saturday to run prayer services for the small Parkchester community. (...)

http://www.tabletmag.com/jewish-life-and-religion/88849/a-bronx-tale-3/

Near the corner of Westchester Avenue and Pugsley Street in Parkchester, just off the elevated tracks of the No. 6 train, Yaakov Wayne Baumann stood outside a graffiti-covered storefront on a chilly Saturday morning. Suited up in a black overcoat with a matching wide-brimmed black fedora, the thickly bearded 42-year-old chatted with elderly congregants as they entered the building for Shabbat service.

The only unusual detail: This synagogue is a mosque.

Or rather, it’s housed inside a mosque. That’s right: Members of the Chabad of East Bronx, an ultra-Orthodox synagogue, worship in the Islamic Cultural Center of North America, which is home to the Al-Iman mosque.

“People have a misconception that Muslims hate Jews,” said Baumann. “But here is an example of them working with us.”

Indeed, though conventionally viewed as adversaries both here and abroad, the Jews and Muslims of the Bronx have been propelled into an unlikely bond by a demographic shift. The borough was once home to an estimated 630,000 Jews, but by 2002 that number had dropped to 45,100, according to a study by the Jewish Community Relations Council. At the same time, the Muslim population has been increasing. In Parkchester alone, there are currently five mosques, including Masjid Al-Iman.

“Nowhere in the world would Jews and Muslims be meeting under the same roof,” said Patricia Tomasulo, the Catholic Democratic precinct captain and Parkchester community organizer, who first introduced the leaders of the synagogue and mosque to each other. “It’s so unique.”

The relationship started years ago, when the Young Israel Congregation, then located on Virginia Avenue in Parkchester, was running clothing drives for needy families, according to Leon Bleckman, now 78, who was at the time the treasurer of the congregation. One of the recipients was Sheikh Moussa Drammeh, the founder of the Al-Iman Mosque, who was collecting donations for his congregants—many of whom are immigrants from Africa. The 49-year-old imam is an immigrant from Gambia in West Africa who came to the United States in 1986. After a year in Harlem, he moved to Parkchester, where he eventually founded the Muslim center and later established an Islamic grade school. Through that initial meeting, a rapport developed between the two houses of worship, and the synagogue continued to donate to the Islamic center, among other organizations.

But in 2003, after years of declining membership, Young Israel was forced to sell its building at 1375 Virginia Ave., according to a database maintained by Yeshiva University, which keeps historical records of synagogues. Before the closing, non-religious items were given away; in fact, among the beneficiaries was none other than Drammeh, who took some chairs and tables for his center.

Meanwhile, Bleckman and the remaining members moved to a nearby storefront location, renting it for $2,000 a month including utilities. With mostly elderly congregants, Young Israel struggled to survive financially and, at the end of 2007, was forced to close for good. The remaining congregants were left without a place to pray. During the synagogue’s farewell service, four young men from the Chabad Lubavitch world headquarters in Crown Heights showed up. Three months earlier, Bleckman, then chairman of the synagogue’s emergency fund, had appealed for help from the Chabad.

“The boys from the Chabad said they came to save us,” said Bleckman. “We were crying.”

At this point, Chabad took over the congregational reins from Young Israel, with members officially adopting the new name Chabad of East Bronx. Still, for the next six to seven weeks, Bleckman said they could not even hold a service because they had nowhere to hold it.

When Drammeh learned of their plight, he immediately volunteered to accommodate them at the Muslim center at 2006 Westchester Ave.—for free.

“They don’t pay anything, because these are old folks whose income are very limited now,” said Drammeh, adding that he felt it was his turn to help the people who had once helped him and his community. “Not every Muslim likes us, because not every Muslim believes that Muslims and Jews should be like this,” Drammeh said, referring to the shared space. But “there’s no reason why we should hate each other, why we cannot be families.” Drammeh in particular admires the dedication of the Chabad rabbis, who walked 15 miles from Brooklyn every Saturday to run prayer services for the small Parkchester community. (...)

http://www.tabletmag.com/jewish-life-and-religion/88849/a-bronx-tale-3/

Jewish Americans Win Alms Race

New research finds Jewish-American families are more likely than those of other faiths to give to charities focusing on basic needs such as food and shelter.

Giving money to the poor is a doctrine of pretty much every religion, but a new study suggests some faiths are better than others at inspiring their followers to actually open their wallets.

Specifically, Jewish families in the U.S. are more likely than their Christian counterparts to contribute to charities focusing on providing basic necessities.

That’s the conclusion of a study by economist Mark Ottoni-Wilhelm, just published in the Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. After controlling for various factors that influence giving, such as income, education and family size, he found support for organizations focusing on food and shelter “does not vary across Christian denominations and nonaffiliated families in any notable way.”

“However, Jewish families are both more likely to give, and, when they do give, give larger amounts,” adds Ottoni-Wilhelm, who is in the economics department of Indiana University-Purdue University - Indianapolis.

Ottoni-Wilhelm’s findings are based on data from the 2001, 2003 and 2005 waves of the Center on Philanthropy Panel Study, part of the Panel Study on Income Dynamics. Among the questions it posed to participants: “Did you, or anyone in your family, make any donation (in the previous year) to organizations that help people in need of food, shelter or other basic necessities?” A follow-up question asked: If so, how much?

He found 29 percent of American families donate to such organizations in a given year, with an average gift of $490. “This 29 percent is made up of three groups,” he notes. “Thirty percent are occasional givers who gave in only one of the three years observed; 37 percent are families who gave in two of the years; and 33 percent are regular givers who gave in all three years.”

So how does this break down in terms of religion? “Although simple descriptions of giving to basic necessity organizations reveal differences across Christian denominational identities,” he writes, “these differences disappear when other differences in income, wealth, ethnicity, etc. are controlled.”

Once those factors were taken out of the equation, Ottoni-Wilhelm found “no differences between Protestant families and Catholic families. No differences between mainline Protestant families and evangelical Protestant families.”

The only exception was Jewish families, who were, on average, significantly more generous than those of other faiths. Ottoni-Wilhelm argues the reason for this most likely lies in the means of persuasion favored by different religious cultures.

For most Christian denominations, arguments for aiding the needy are generally framed in terms of “stewardship, duty and reciprocity,” he writes, adding there is no evidence that any of those approaches are effective. The appeals to duty provided by pastors “are especially weak, because they do not frame that duty as a part of the member’s religious identity,” he argues.

In contrast, “Jewish philanthropy uses appeals to be generous that align well” with social-science research on how to effectively frame a request for help. He notes that Jewish appeals often connect “the needs of people who are poor to the Jewish history of enslavement in Egypt,” effectively forming an empathetic connection between the person giving money and the person receiving it.

Furthermore, “The literature on Jewish philanthropy emphasizes that giving to help people with basic needs is an essential part of Jewish identity,” he notes. “(It also) emphasizes a strong community norm behind giving.”

The apparent effectiveness of these appeals, alone or in combination, “might suggest ideas that can be transferred to other religious identities” looking for ways to encourage charitable giving, Ottani-Wilhelm concludes. Given the level of need in these tough economic times, such experimentation can’t come quickly enough.

http://www.miller-mccune.com/culture/jewish-americans-win-alms-race-22297

Giving money to the poor is a doctrine of pretty much every religion, but a new study suggests some faiths are better than others at inspiring their followers to actually open their wallets.

Specifically, Jewish families in the U.S. are more likely than their Christian counterparts to contribute to charities focusing on providing basic necessities.

That’s the conclusion of a study by economist Mark Ottoni-Wilhelm, just published in the Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. After controlling for various factors that influence giving, such as income, education and family size, he found support for organizations focusing on food and shelter “does not vary across Christian denominations and nonaffiliated families in any notable way.”

“However, Jewish families are both more likely to give, and, when they do give, give larger amounts,” adds Ottoni-Wilhelm, who is in the economics department of Indiana University-Purdue University - Indianapolis.

Ottoni-Wilhelm’s findings are based on data from the 2001, 2003 and 2005 waves of the Center on Philanthropy Panel Study, part of the Panel Study on Income Dynamics. Among the questions it posed to participants: “Did you, or anyone in your family, make any donation (in the previous year) to organizations that help people in need of food, shelter or other basic necessities?” A follow-up question asked: If so, how much?

He found 29 percent of American families donate to such organizations in a given year, with an average gift of $490. “This 29 percent is made up of three groups,” he notes. “Thirty percent are occasional givers who gave in only one of the three years observed; 37 percent are families who gave in two of the years; and 33 percent are regular givers who gave in all three years.”

So how does this break down in terms of religion? “Although simple descriptions of giving to basic necessity organizations reveal differences across Christian denominational identities,” he writes, “these differences disappear when other differences in income, wealth, ethnicity, etc. are controlled.”

Once those factors were taken out of the equation, Ottoni-Wilhelm found “no differences between Protestant families and Catholic families. No differences between mainline Protestant families and evangelical Protestant families.”

The only exception was Jewish families, who were, on average, significantly more generous than those of other faiths. Ottoni-Wilhelm argues the reason for this most likely lies in the means of persuasion favored by different religious cultures.

For most Christian denominations, arguments for aiding the needy are generally framed in terms of “stewardship, duty and reciprocity,” he writes, adding there is no evidence that any of those approaches are effective. The appeals to duty provided by pastors “are especially weak, because they do not frame that duty as a part of the member’s religious identity,” he argues.

In contrast, “Jewish philanthropy uses appeals to be generous that align well” with social-science research on how to effectively frame a request for help. He notes that Jewish appeals often connect “the needs of people who are poor to the Jewish history of enslavement in Egypt,” effectively forming an empathetic connection between the person giving money and the person receiving it.

Furthermore, “The literature on Jewish philanthropy emphasizes that giving to help people with basic needs is an essential part of Jewish identity,” he notes. “(It also) emphasizes a strong community norm behind giving.”

The apparent effectiveness of these appeals, alone or in combination, “might suggest ideas that can be transferred to other religious identities” looking for ways to encourage charitable giving, Ottani-Wilhelm concludes. Given the level of need in these tough economic times, such experimentation can’t come quickly enough.

http://www.miller-mccune.com/culture/jewish-americans-win-alms-race-22297

dimanche 8 avril 2012

Holocaust survivors in L.A are still struggling

BY JANE ULMAN

http://www.jewishjournal.com/ community_briefs/article/holocaust_survivors_in_la_are_still_struggling_20071130/

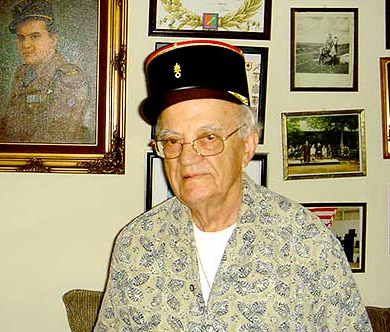

Joe Knobler. Photos by Jane Ulman

Joshua "Joe" Knobler used to go salsa dancing three times a week. He used to play cards with the guys every day. Now, 88, with both his health and finances failing, he sits home all day in his drab one-room apartment in Valley Village watching television.

"Television is my life," he said.

A Holocaust survivor who spent five years in Buchenwald, Knobler was married and divorced twice; both spouses are now deceased, and he is estranged from his children. He leaves his apartment door open all day, but no one stops by to say hello.

Knobler says he doesn't have enough money each month to buy food, get his clothes cleaned or purchase more than a single $5 can of bug spray to fight the cockroaches infesting his apartment.

Knobler used to make a decent living as a tailor. His industrial Singer sewing machine sits in the corner of his one-room apartment, now overcrowded with a queen-size bed, a hospital bed, a dresser and a couch. He explains that the sewing machine is broken; he can't afford a new needle.

He receives $939 in SSI (Supplemental Security Income) each month and pays $639 in rent. Of the $300 remaining, he spends $30 for the telephone, $60 for cable television and another $30 for medication, mostly for pain pills. He's had two back surgeries, one only 10 months ago, and lives with debilitating chronic pain. He has $2.44 in the bank.

"I don't get from nobody," he said.

But that's not exactly true; Knobler has been a Jewish Family Service (JFS) client for the past 10 years, part of the Survivors of the Holocaust Program. He receives eight hours a week in home care services, a monthly $100 Ralphs gift card and $50 a month in taxi vouchers. Additionally, a bag of groceries from SOVA is delivered to his apartment once a month.

Knobler, in fact, receives $2,500 a year in support services, an amount that has been capped for all indigent Holocaust survivors by the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany, which provides $914,000 to JFS in Los Angeles annually to assist needy survivors.

But Knobler has actually received $5,300 in services already this year, thanks to two funds specifically earmarked for emergencies and other essentials for the estimated 3,000 poverty-stricken Holocaust survivors in Los Angeles.

For Knobler, these additional expenses included ambulance transportation (not reimbursed by Medi-Cal because of an unknown glitch in his citizenship papers filed in 1951, a problem being rectified by JFS) and new glasses.

One fund was created by Roz and Abner Goldstine, longtime JFS board members, who donated $250,000 after reading about the plight of Los Angeles' 3,000 indigent Holocaust survivors in a story last year in The Jewish Journal.